|

. . . or, all about the genus equus, subgenus

asinus-like behavior of all those hee-hawing non-photographers who have managed to

barge their way uninvited into my personal space, disrupt my concentration and

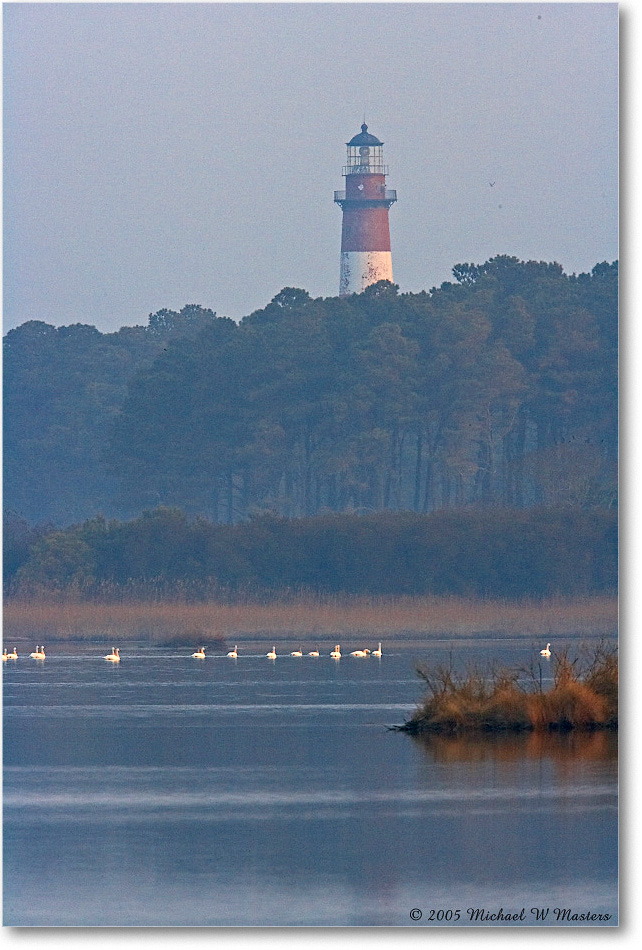

wreck the warm, fuzzy creative glow that comes from photographing some

never-to-be-seen-again (at least not by me) marvel of nature that I had just

spent hours (exaggeration alert!) trying to get close enough to capture

in digits. . . . or, all about the genus equus, subgenus

asinus-like behavior of all those hee-hawing non-photographers who have managed to

barge their way uninvited into my personal space, disrupt my concentration and

wreck the warm, fuzzy creative glow that comes from photographing some

never-to-be-seen-again (at least not by me) marvel of nature that I had just

spent hours (exaggeration alert!) trying to get close enough to capture

in digits.

Given the subject matter, readers may wonder why I

haven't titled this essay

"A*$h@ Besides, the great majority of those who stop to chat

when I'm in the field with my big lens rig aren't disruptive by intent, they're just well-meaning folks, drawn

to photographers like any other set of groupies. Sort of thrill by

association, I guess. So I'll make do with the milder donkey epithet out of respect for those

who honestly mean no harm but rather

approach photographers out of ignorance for the disruption they cause

when

the photographer happens to be doing something critical. Besides, the great majority of those who stop to chat

when I'm in the field with my big lens rig aren't disruptive by intent, they're just well-meaning folks, drawn

to photographers like any other set of groupies. Sort of thrill by

association, I guess. So I'll make do with the milder donkey epithet out of respect for those

who honestly mean no harm but rather

approach photographers out of ignorance for the disruption they cause

when

the photographer happens to be doing something critical.

And, in many cases people are genuinely looking for a

learning experience. For such people, I am only too

happy to oblige -- with perhaps

more detail than was

wanted, as my daughter will certainly attest while

rolling her eyes in mock disgust! wanted, as my daughter will certainly attest while

rolling her eyes in mock disgust!

But, you donkeys out there,

those among you who have plagued me with your snide remarks and your nosy questions

about the cost of my gear and your untimely and persistent interruptions

despite the fact that I'm clearly in the midst of something requiring

complete concentration, interruptions that have let that

special bird swim just beyond the perfect sun angle while you are

soliciting, nay, demanding my attention -- you

know what you really are!

We've All Been There

I'm sure every nature photographer has had similar

experiences. That once-in-a-decade spotted sandpiper (or whatever) you've

been approaching low and slow for fifteen minutes with your supertelephoto

rig has finally stopped eyeing you suspiciously, and you've put eye to viewfinder, the

perfect frame-filling composition now in view. Suddenly, you see alarm in

the bird's posture. You hardly have time to reflect that you've done

nothing to cause the bird distress when, BAM, the creature explodes to wing

and is gone.

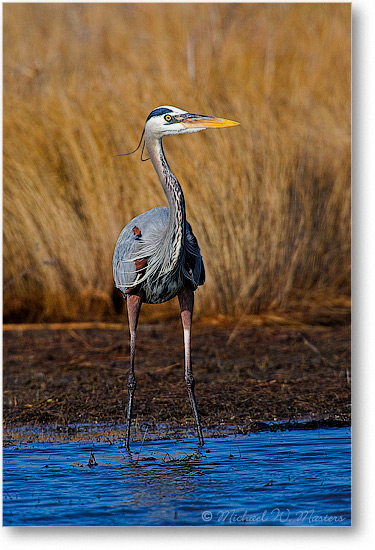

Almost simultaneously a braying voice behind you announces, practically in

your ear, "Hey buddy, there's a heron back down the road! You should

come take a picture of it. With that camera I bet you can photograph it from a mile away! Yuk, yuk, yuk!" I'm sure every nature photographer has had similar

experiences. That once-in-a-decade spotted sandpiper (or whatever) you've

been approaching low and slow for fifteen minutes with your supertelephoto

rig has finally stopped eyeing you suspiciously, and you've put eye to viewfinder, the

perfect frame-filling composition now in view. Suddenly, you see alarm in

the bird's posture. You hardly have time to reflect that you've done

nothing to cause the bird distress when, BAM, the creature explodes to wing

and is gone.

Almost simultaneously a braying voice behind you announces, practically in

your ear, "Hey buddy, there's a heron back down the road! You should

come take a picture of it. With that camera I bet you can photograph it from a mile away! Yuk, yuk, yuk!"

That really is how he laughs. "Yuk, yuk, yuk!"

You look longingly at the now diminishing spec that

once held your hopes for a thrilling and productive photo session and then

prepare to turn and face

this particular donkey that is today's tormentor. But first you have

to get up. Having spent the last quarter hour in a crouched position,

inching slowly forward, the

knees don't seem to want to cooperate. As you struggle

awkwardly to your feet you worry vaguely that you're making yourself

look weak and unmanly in front of what might turn out to be some young and

virile muscle bound macho specimen who's hand holding one of Canon's vintage 1200mm f5.6 telephoto behemoths, all 36 lb

of it -- a surefire way to find yourself at a psychological

disadvantage in the exchange that is certain to follow. You look longingly at the now diminishing spec that

once held your hopes for a thrilling and productive photo session and then

prepare to turn and face

this particular donkey that is today's tormentor. But first you have

to get up. Having spent the last quarter hour in a crouched position,

inching slowly forward, the

knees don't seem to want to cooperate. As you struggle

awkwardly to your feet you worry vaguely that you're making yourself

look weak and unmanly in front of what might turn out to be some young and

virile muscle bound macho specimen who's hand holding one of Canon's vintage 1200mm f5.6 telephoto behemoths, all 36 lb

of it -- a surefire way to find yourself at a psychological

disadvantage in the exchange that is certain to follow.

On your feet at last, you look him up and down and

your worries about appearing unmanly vanish. What stands before

you is, all in all, a quite representative example of

donkeydom -- plaid shorts and a flowery shirt topped by a straw hat, all

supported on pale spindly legs, knobby knees and flip flops.

Unfortunately, none of the colors match. (Don't the wives/keepers of

these equine misfits ever monitor how their charges are released into the

wild?) Instead, you're just sad over yet another lost

opportunity and annoyed that the denouement of the whole sorry episode is

that you have to deal with this misbegotten creature. And, he's still

there, waiting expectantly for your words of

approbation at the delivery of this vital information. Which, from the

expression on his face, he apparently judges will surely save

your presumably until now worthless photographic career from oblivion. On your feet at last, you look him up and down and

your worries about appearing unmanly vanish. What stands before

you is, all in all, a quite representative example of

donkeydom -- plaid shorts and a flowery shirt topped by a straw hat, all

supported on pale spindly legs, knobby knees and flip flops.

Unfortunately, none of the colors match. (Don't the wives/keepers of

these equine misfits ever monitor how their charges are released into the

wild?) Instead, you're just sad over yet another lost

opportunity and annoyed that the denouement of the whole sorry episode is

that you have to deal with this misbegotten creature. And, he's still

there, waiting expectantly for your words of

approbation at the delivery of this vital information. Which, from the

expression on his face, he apparently judges will surely save

your presumably until now worthless photographic career from oblivion.

Sadly, he probably never even saw your intended subject.

You pause imperceptibly, and in that moment you are

deciding whether to take the Mother Teresa fork in the road of interpersonal

relational ethics and thank him

graciously for the information he has offered or do what you really want

to do and flay his donkey hide with the whip of truth. Namely, that you

already have dozens of very fine heron images in your portfolio and you

don't need an immediately deletable image of a bird situated 50 yards off the road, on a

mud flat, backlit by the Sun and framed against ragged vegetation that

cannot be eliminated from the composition.

Never one to harm poor suffering beasts, you opt not

to follow the flogging fork in the interpersonal ethical road. You

avert you eyes and mutter something noncommittal about having seen the heron

on your way past the marsh where it was located. With this reply, his eyes first

take on a puzzled look and then the expectant smile slowly fades as the idea

dawns on him that you do not value the sighting he has brought. It's not

that you already knew about the heron that is bothering him. He's read from

your evasive tone of voice and your defensive body language that, having

seen it you didn't consider it worth stopping to photograph. You

didn't actually have to say this. Donkeys can infer such things

quicker than a clinically trained psychoanalyst. Never one to harm poor suffering beasts, you opt not

to follow the flogging fork in the interpersonal ethical road. You

avert you eyes and mutter something noncommittal about having seen the heron

on your way past the marsh where it was located. With this reply, his eyes first

take on a puzzled look and then the expectant smile slowly fades as the idea

dawns on him that you do not value the sighting he has brought. It's not

that you already knew about the heron that is bothering him. He's read from

your evasive tone of voice and your defensive body language that, having

seen it you didn't consider it worth stopping to photograph. You

didn't actually have to say this. Donkeys can infer such things

quicker than a clinically trained psychoanalyst.

His fading smile morphs at last into a sullen frown,

his eyes narrow to slits and he fixes you with a malevolent glare. Somehow you know what's coming

next. It's all going to be your fault. "Well," he

intones in disgust as he prepares to turn away, "I thought a real

photographer would want to know where the good stuff is." And with

that he stalks off, flip-flops smacking against the bottom of his heels.

You're left to pack up and wonder how you could have handled the interaction

in a way that satisfied this asinus intruder while keeping your own frustration at the

lost opportunity from spilling over.

And, when you'll ever see another spotted sandpiper!

Credit Where Credit's Due

To give credit where it is due, this essay is devoted to one special

donkey whose antics, after years of being subjected to the hit-and-run

buffoonery of other donkeys in the

wild, finally prompted the writing of this testimonial to our equine

brethren. Needless to say, it was but the most recent in a long line

of many such incidents. This particular asinus was a

passenger in a car that drove by as I was loading my big lens bird rig into

my SUV at the beach collocated with my favorite refuge. I happened to

glance toward the car as it approached. The passenger window rolled

down and the vapid face of a teenager or twenty-something leaned out.

Having evidently seen the size of the big lens, the face of the occupant

contorted into an enormous toothy grin, resembling that of a jackass in full

grimace, and brayed, "CHEEEESE." With that the car was gone -- the

donkey inside no doubt hee-hawing uproariously at his oh-so-original gag -- and a resolve was

born that had begun to germinate earlier in the day. To give credit where it is due, this essay is devoted to one special

donkey whose antics, after years of being subjected to the hit-and-run

buffoonery of other donkeys in the

wild, finally prompted the writing of this testimonial to our equine

brethren. Needless to say, it was but the most recent in a long line

of many such incidents. This particular asinus was a

passenger in a car that drove by as I was loading my big lens bird rig into

my SUV at the beach collocated with my favorite refuge. I happened to

glance toward the car as it approached. The passenger window rolled

down and the vapid face of a teenager or twenty-something leaned out.

Having evidently seen the size of the big lens, the face of the occupant

contorted into an enormous toothy grin, resembling that of a jackass in full

grimace, and brayed, "CHEEEESE." With that the car was gone -- the

donkey inside no doubt hee-hawing uproariously at his oh-so-original gag -- and a resolve was

born that had begun to germinate earlier in the day.

It had been a slow day and I was using my

300mm on a beanbag inside my car to photograph laughing gulls on a fence

separating lanes at the beach parking lot. Laughing gulls are my

favorites because of their beautiful wine colored bills, legs and eye

orbital rings and their high contrast black, white and gray plumage. That day,

gulls were lined up on practically every fence post. Because beach

gulls are so acclimatized to cars and people one can get very close without

bothering them if one approaches slowly. Things were going great. Then, along came a kid

with a stick. He began whacking every fence post, frightening away

each gull in turn, as if it were a game. Soon, there It had been a slow day and I was using my

300mm on a beanbag inside my car to photograph laughing gulls on a fence

separating lanes at the beach parking lot. Laughing gulls are my

favorites because of their beautiful wine colored bills, legs and eye

orbital rings and their high contrast black, white and gray plumage. That day,

gulls were lined up on practically every fence post. Because beach

gulls are so acclimatized to cars and people one can get very close without

bothering them if one approaches slowly. Things were going great. Then, along came a kid

with a stick. He began whacking every fence post, frightening away

each gull in turn, as if it were a game. Soon, there were

no gulls to photograph. A donkey in the making, if ever there was one. were

no gulls to photograph. A donkey in the making, if ever there was one.

My resolve was finalized the next day, the last of this particular trip.

The entire week had been poor; wind and rain had left me with few memorable

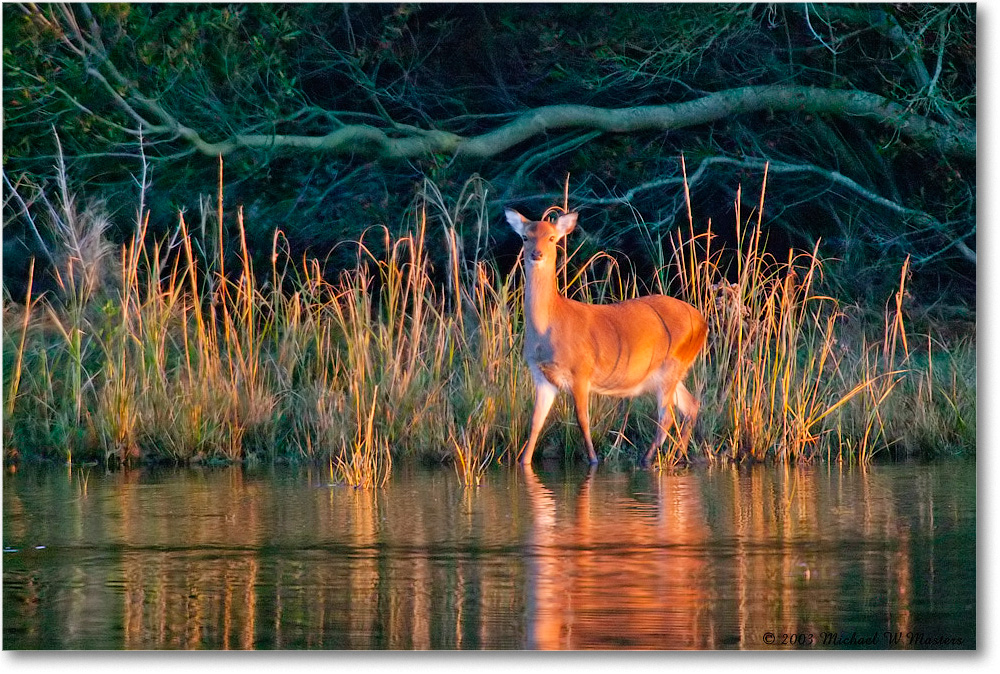

images to show for the effort. But that final day dawned

calm and sunny. I was out early and was happy to see plenty of

activity. I soon spotted a trio of oystercatchers on a strip of

cove beach away from the ocean. This is an ideal setting, sheltered from wind

and waves, and there's green marsh grass in the distant background, depending on angle of

view. I have made many of my best images here over the years.

Just as I getting my rig out of my SUV I noticed a mother and young

daughter heading across the sand to the cove. I wasn't sure what they were after. Possibly it was seashells, because

mother began looking down carefully as she walked along the beach. If

so, the nearby Atlantic Ocean beach would have offered better prospects by

far. This wasn't good, but the beach was fairly long, and if they stayed

away from the oystercatchers I might still be able to approach the OCs.

I finished putting the rig together and started toward the beach.

Could mother and daughter, oystercatchers and I coexist? Sadly, the

answer was no. Just as I getting my rig out of my SUV I noticed a mother and young

daughter heading across the sand to the cove. I wasn't sure what they were after. Possibly it was seashells, because

mother began looking down carefully as she walked along the beach. If

so, the nearby Atlantic Ocean beach would have offered better prospects by

far. This wasn't good, but the beach was fairly long, and if they stayed

away from the oystercatchers I might still be able to approach the OCs.

I finished putting the rig together and started toward the beach.

Could mother and daughter, oystercatchers and I coexist? Sadly, the

answer was no.

Soon they were walking directly toward the oystercatchers, which

were by now distinctly alarmed. The OCs began scurrying away, running

rather than flying, thankfully. My chances were

plummeting by the moment -- but I kept going because, well, they hadn't

flown yet and oystercatchers are among the most striking of shorebirds.

And then it happened. The daughter

broke into a run directly at the

OCs, waving her arms wildly, clearly intending to flush them. Another

child playing a game with wildlife -- and the effect was the same. The oystercatchers were

gone for good. broke into a run directly at the

OCs, waving her arms wildly, clearly intending to flush them. Another

child playing a game with wildlife -- and the effect was the same. The oystercatchers were

gone for good.

Perhaps the saddest part of this situation was not my lost photographic

opportunity -- although that stung, because it was to be the best setting I

would encounter

all day -- but rather the fact that the child's mother paid not the

slightest attention to her daughter's inappropriate behavior toward wildlife. And, I might add, no wonder oystercatchers are among the

most skittish of shorebirds -- at least at this refuge.

So you see how it is, dear reader, that I came to write this essay.

My First Donkey Encounter

My first

ever encounter with a donkey, an individual who surely qualified for the more

biting appellation

that shall not be mentioned in print, came early in my days of bird

photography, at my favorite photo location, a place I call Egret Alley.

It is a pool located along a channel at one of the east coast refuges. The

configuration is such that a channel connects the pool to a managed

impoundment for waterfowl, waders, shorebirds, etc. There is also a culvert

that links the pool, eventually via and a long,

meandering stream, to the Atlantic Ocean.

Flow thorough the culvert is managed by refuge staff

so that unless there is excess rainwater to be drained off the pool is

usually still. There is always a supply of fresh fish from the

impoundment, and there is also a small sandbar at the pool, which makes for an ideal fishing habitat for

herons and, especially, egrets. Hence, the name, Egret Alley. Flow thorough the culvert is managed by refuge staff

so that unless there is excess rainwater to be drained off the pool is

usually still. There is always a supply of fresh fish from the

impoundment, and there is also a small sandbar at the pool, which makes for an ideal fishing habitat for

herons and, especially, egrets. Hence, the name, Egret Alley.

One sunny summer morning, with the Sun in excellent

position for frontal lighting and with blue sky reflecting off

the water, I found a tolerant snowy egret that allowed me

to gain access down the bank and onto the sand bar without flushing. I

was close enough for what I hoped would be outstanding frame filling images

with the only "long lens" I could afford at the time, my

tripod-mounted 200mm APO! This was in the days prior to image

stabilization, and even with a 200mm lens and teleconverer I always used a

tripod.

Just as I put eye to viewfinder, with bird totally

comfortable with my presence, there was a huge SPLASH! The snowy was

gone in a heartbeat, winging away down the channel. I looked out to see most of the pool covered with an enormous fishnet.

Dumbfounded, I scanned the top of the bank -- to find a most unwelcome equus

asinus standing there, an amused, mocking expression on his face.

"Don't worry," he brayed smugly. "He'll come back." And he ambled away,

hooves clicking and tail switching flies away. Just as I put eye to viewfinder, with bird totally

comfortable with my presence, there was a huge SPLASH! The snowy was

gone in a heartbeat, winging away down the channel. I looked out to see most of the pool covered with an enormous fishnet.

Dumbfounded, I scanned the top of the bank -- to find a most unwelcome equus

asinus standing there, an amused, mocking expression on his face.

"Don't worry," he brayed smugly. "He'll come back." And he ambled away,

hooves clicking and tail switching flies away.

Of course, the snowy never did return. But it

didn't matter because the fishnet now covered the best part of the fishing

area, ensuring that no bird would fish there anyway. I have to admit,

I was sorely tempted to take that fish net and toss it onto the bank.

But, I was none too sure how the refuge staff would view such an action if

the hee-haw reported it. In the end, I could do no more than retreat to my vehicle to reflect on the

fact that, like kudzu, fishermen are an invasive species and will drive out

birds and photographers wherever there are fish to be found. Of course, the snowy never did return. But it

didn't matter because the fishnet now covered the best part of the fishing

area, ensuring that no bird would fish there anyway. I have to admit,

I was sorely tempted to take that fish net and toss it onto the bank.

But, I was none too sure how the refuge staff would view such an action if

the hee-haw reported it. In the end, I could do no more than retreat to my vehicle to reflect on the

fact that, like kudzu, fishermen are an invasive species and will drive out

birds and photographers wherever there are fish to be found.

After mulling over this newly discovered and sad reality of

life, I began

searching elsewhere for another egret.

What Donkeys Do

Over the years I've had many people come up to me in

the field and

ask questions. The most common ones are, how much does that big lens

rig cost and, how far can you see with it.

If the latter question is asked, and if I'm not doing much I let them take a look

through the viewfinder. Most people are vaguely disappointed once

they've had a view, especially if the subject is distant. Even a 600mm

with a 2X gives only the equivalent view of 24X magnification on a full

frame camera, far short of

the view offered by the 60X spotting scopes that birders routinely use. Over the years I've had many people come up to me in

the field and

ask questions. The most common ones are, how much does that big lens

rig cost and, how far can you see with it.

If the latter question is asked, and if I'm not doing much I let them take a look

through the viewfinder. Most people are vaguely disappointed once

they've had a view, especially if the subject is distant. Even a 600mm

with a 2X gives only the equivalent view of 24X magnification on a full

frame camera, far short of

the view offered by the 60X spotting scopes that birders routinely use.

I try to be patient with people who ask about money,

but I'm just naturally reticent when it comes to revealing the cost of a

bird capable rig to a total stranger. Anyone who has priced a Canon or

Nikon 500mm, 600mm or 800mm lens, a pro digital body, a carbon fiber tripod

and a gimbal head, along with the requisite flash, flash arm and external battery for

flash fill, knows how much these rigs can cost. So I try to give a

noncommittal reply (hopefully with a smile), something like, "More than I

can afford!" or maybe I answer a question with a question. "How much

do you think?" Inevitably people guess radically too low. "A

grand at least!" "Yeah, that's about right," I reply

with a deadpan voice, and the

problem is solved. I try to be patient with people who ask about money,

but I'm just naturally reticent when it comes to revealing the cost of a

bird capable rig to a total stranger. Anyone who has priced a Canon or

Nikon 500mm, 600mm or 800mm lens, a pro digital body, a carbon fiber tripod

and a gimbal head, along with the requisite flash, flash arm and external battery for

flash fill, knows how much these rigs can cost. So I try to give a

noncommittal reply (hopefully with a smile), something like, "More than I

can afford!" or maybe I answer a question with a question. "How much

do you think?" Inevitably people guess radically too low. "A

grand at least!" "Yeah, that's about right," I reply

with a deadpan voice, and the

problem is solved.

Perhaps the next most common interruption is from

people asking for bird identifications -- and these I almost always try to

make time for. For the places I go, I usually have the right answer

and I do like to help out those who are interested enough to want to know a

bird's ID. However, I have to admit that one of my most embarrassing

moments came in a somewhat related situation.

A Ruddy June

It was a June afternoon and I happened on a male and

two female ruddy ducks in summer breeding plumage at a managed pool at

one of my favorite refuges, a place my family and I have been making an

annual June Father's Day pilgrimage to for 20 years. It was the only

time I had ever seen ruddys in summer plumage, so I was frantic not to miss

this opportunity. I parked on the shoulder and set up as quickly and as unobtrusively

as possible. It was a June afternoon and I happened on a male and

two female ruddy ducks in summer breeding plumage at a managed pool at

one of my favorite refuges, a place my family and I have been making an

annual June Father's Day pilgrimage to for 20 years. It was the only

time I had ever seen ruddys in summer plumage, so I was frantic not to miss

this opportunity. I parked on the shoulder and set up as quickly and as unobtrusively

as possible.

The ruddys were some distance off shore, cruising

back and forth, but well aware of my presence. The sun angle was

forty-five degrees or so off-axis, which meant that getting a good image was

a matter of careful timing -- waiting for the right body posture and head

turn. I was on the shoulder of a beach access road, so there was constant

traffic behind me, which meant that at any time this beautiful little trio

might be spooked, take to wing and disappear. It was a nerve wracking

experience.

They

had made a pass down sun and were returning when I heard a car stop behind

me and a door close. The ruddys reacted by bending their path outward

from the shore, and I groaned inwardly but kept eye to viewfinder.

They were slowly increasing their distance from shore and getting smaller in

frame with each passing second, but I continued pressing the shutter release

each time the male, largest of the three, looked my way and the sun glinted

in his eye. Then, right behind me someone asked, "Hey, have you ever

seen ruddy ducks in breeding plumage like that here in June?" They

had made a pass down sun and were returning when I heard a car stop behind

me and a door close. The ruddys reacted by bending their path outward

from the shore, and I groaned inwardly but kept eye to viewfinder.

They were slowly increasing their distance from shore and getting smaller in

frame with each passing second, but I continued pressing the shutter release

each time the male, largest of the three, looked my way and the sun glinted

in his eye. Then, right behind me someone asked, "Hey, have you ever

seen ruddy ducks in breeding plumage like that here in June?"

Now, I'll have to admit that

at this point I was no

longer a civilized being, governed by the rules of polite society.

Even though this guy sounded like a really decent fellow and was obviously

educated enough in bird lore to know that ruddys in summer dress were out of

season at this time and at this location, none of that mattered. Some atavistic part of my brain had

taken over and all I could think of was capturing as many images of that beautiful

male ruddy duck before it got too far away to be large enough in

frame to be interesting. Now, I'll have to admit that

at this point I was no

longer a civilized being, governed by the rules of polite society.

Even though this guy sounded like a really decent fellow and was obviously

educated enough in bird lore to know that ruddys in summer dress were out of

season at this time and at this location, none of that mattered. Some atavistic part of my brain had

taken over and all I could think of was capturing as many images of that beautiful

male ruddy duck before it got too far away to be large enough in

frame to be interesting.

But the donkey, be he ever so fine a fellow,

nonetheless had to be dealt with.

What to do? How to end all conversation immediately without resort to

overt rudeness or more extreme measures -- which, of course, would require

that I abandon the viewfinder, however momentarily? Out of the

depths of the necessity of the situation, and almost without conscious

thought, the answer issued forth unbidden from my lips.

"I've never been here in June."

Behind me there was silence. I kept shooting.

Soon there came the sounds of a door closing, engine engaging, gravel

crunching and car pulling away. But this barely registered. I

made image after image as the ruddys gently swam in an avoiding arc around

my position and continued away, not to return. I chimped through the

files and realized with satisfaction that, although with the off-axis sun

angle some extra effort would be required in post processing there were

probably some good results from this miraculous ruddy apparition. Behind me there was silence. I kept shooting.

Soon there came the sounds of a door closing, engine engaging, gravel

crunching and car pulling away. But this barely registered. I

made image after image as the ruddys gently swam in an avoiding arc around

my position and continued away, not to return. I chimped through the

files and realized with satisfaction that, although with the off-axis sun

angle some extra effort would be required in post processing there were

probably some good results from this miraculous ruddy apparition.

Then, a thought began to nag at me. I really had been rude to that guy, donkey though he may have been, and intrusion

on a once-in-20-years photo opportunity though he may have posed. And, I

had blurted out a "little white lie" too -- something that didn't sit

well

in retrospect, even if it had come in the expediency of the moment and as a means of

insuring that I could harvest a few more precious images of those glorious

ruddys.

Of course, there was the fact that in a perfect world he should have know

better than to interrupt someone with obvious serious intent as evidenced by

the big lens rig. But still, my reply now felt wrong, and I lamented

that I had let irritation guide the outcome. It would have taken only

a few seconds more to say something like, "I've been coming here 20 years

and this is the first time I've seen ruddys in breeding plumage in June." wrong, and I lamented

that I had let irritation guide the outcome. It would have taken only

a few seconds more to say something like, "I've been coming here 20 years

and this is the first time I've seen ruddys in breeding plumage in June."

I was happy with the ruddy images but it definitely

was not my finest hour in interpersonal relationships. I had the

distinct feeling that while I was not a donkey I might well deserve my own

place somewhere in the barnyard. From this uncomfortable feeling came a resolve

to grit my teeth and meet each request with at least a modicum of

politeness, no matter the cost in missed images.

Blasting the Ducks

Perhaps the most egregious example of donkeydom I

have ever run across happened several years ago, once again at my favorite

refuge. This time, although the encounter resulted in a lost

opportunity for me the more important point has to do with photographer

interaction with wildlife. My observation is that most nature

photographers are very respectful of nature. But we all know of

exceptions -- and we also all know that a few bad examples can make life

miserable for the rest of us. All it takes is one smartphone video

posted to Internet or one negative thread on a birding forum or one incident

reported to authorities at a park or refuge to compromise the prospects for

all of us. Perhaps the most egregious example of donkeydom I

have ever run across happened several years ago, once again at my favorite

refuge. This time, although the encounter resulted in a lost

opportunity for me the more important point has to do with photographer

interaction with wildlife. My observation is that most nature

photographers are very respectful of nature. But we all know of

exceptions -- and we also all know that a few bad examples can make life

miserable for the rest of us. All it takes is one smartphone video

posted to Internet or one negative thread on a birding forum or one incident

reported to authorities at a park or refuge to compromise the prospects for

all of us.

I know that personally I try to approach all wildlife

as slowly and as quietly as possible. And, of course, there is no

substitute for knowing one's subjects. For me, wildlife is almost

exclusively birds, and in just about any situation one can usually tell by

the behavior of the subject whether one can approach and how near one can

get. In the early years I inevitably tried to get too close too soon.

Now, I move very slowly, keeping the camera between my face and the subject,

and using any obstacle as a temporary blind to move a few steps closer

whenever possible. Of course, some birds are wary no matter what, but

more often than not I can get as close as I need to. Sometimes the problem becomes one of the bird

falling asleep when what I really want is a nice alert portrait image!

I'm sure other long time bird photographers could relate similar stories -- it just

takes patience and understanding of the subject. I know that personally I try to approach all wildlife

as slowly and as quietly as possible. And, of course, there is no

substitute for knowing one's subjects. For me, wildlife is almost

exclusively birds, and in just about any situation one can usually tell by

the behavior of the subject whether one can approach and how near one can

get. In the early years I inevitably tried to get too close too soon.

Now, I move very slowly, keeping the camera between my face and the subject,

and using any obstacle as a temporary blind to move a few steps closer

whenever possible. Of course, some birds are wary no matter what, but

more often than not I can get as close as I need to. Sometimes the problem becomes one of the bird

falling asleep when what I really want is a nice alert portrait image!

I'm sure other long time bird photographers could relate similar stories -- it just

takes patience and understanding of the subject.

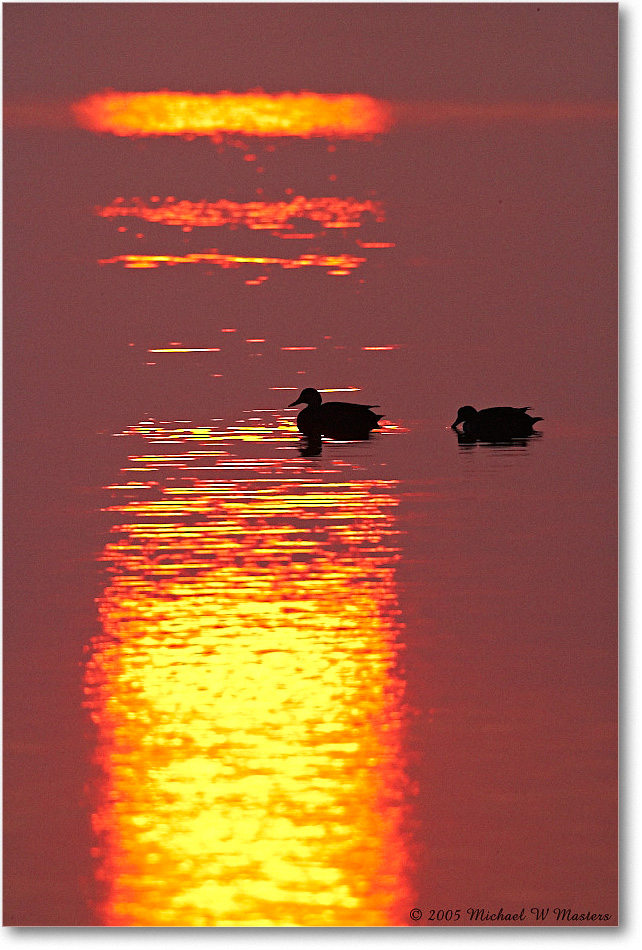

In this particular instance, I had spotted a pair of

mated mallards swimming in a channel alongside a busy beach access road.

In fact, the channel was next to a parking lot which was across the street

from the beach visitor center, so there were plenty of parked cars to serve

as blinds. Mallards at this refuge are notoriously flighty, and being

situated in a heavily trafficked area I knew that the slightest disturbance

would flush them. So I parked some distance away and set up my

big lens rig. I could have gone with a shorter lens hand-held

but I opted for the big rig for greater standoff, hoping to minimize the

likelihood of flushing them. As it turned out, I needn't have

bothered. In this particular instance, I had spotted a pair of

mated mallards swimming in a channel alongside a busy beach access road.

In fact, the channel was next to a parking lot which was across the street

from the beach visitor center, so there were plenty of parked cars to serve

as blinds. Mallards at this refuge are notoriously flighty, and being

situated in a heavily trafficked area I knew that the slightest disturbance

would flush them. So I parked some distance away and set up my

big lens rig. I could have gone with a shorter lens hand-held

but I opted for the big rig for greater standoff, hoping to minimize the

likelihood of flushing them. As it turned out, I needn't have

bothered.

I moved slowly from car to car, carrying the long

lens and tripod and taking care to remain hidden from the mallards. At

last I was ready to place the tripod ahead of me around the last car and

ease behind it. At that moment, a most reprehensible donkey appeared

from nowhere, running literally at a sprint and shouting with glee as he

came, holding a camera to his eye with what appeared to be a 70-200mm zoom

attached and blasting away at full high speed continuous shutter release.

Whack-whack-whack-whack-whack. He slid feet first down the shallow

bank of the channel, a mere three feet or so to  waters edge, like a runner

sliding into second base, continuing to blast away all the way to the

bottom. Needless to say, by the time he reached water's edge the panicked mallards had exploded into the air, wings beating

wildly. waters edge, like a runner

sliding into second base, continuing to blast away all the way to the

bottom. Needless to say, by the time he reached water's edge the panicked mallards had exploded into the air, wings beating

wildly.

I watched this disturbing spectacle with a mix of

disbelief, horror, disgust, disappointment and a sense of uncertainty as to how to react.

Was this guy really that stupid? Should I say something to him?

If I did, how would he react? After all, I didn't wear an official hat

there. Should I report it to the park rangers? The beach visitor

center was just across the street. And then, there was the fact that

this individual's ancestral beginnings were clearly different than mine.

What exactly would be the outcome of a cross-cultural encounter under such

circumstances? While I pondered these existential questions, he

climbed up from second base and walked away without so much as a glance in

my direction,

despite big lens and tripod as well as my person being clearly

visible from his vantage. despite big lens and tripod as well as my person being clearly

visible from his vantage.

To this day I do not know what I should have done.

Nor do I particularly mourn the lost imaging opportunity -- even though

mallards are difficult at that refuge, and even though I had spent considerable time

working my way into a favorable position. What sticks with me

is the panicked flight of those mallards and the casual and unconcerned,

almost nonchalant way this particular individual sauntered away once they

were gone.

Shoe on Other Foot

I've always been an amateur, a hobbyist, with no

desire to become a "pro." But, in earlier years, after I could afford

a big lens, and as I was starting to actually develop some skills (big

acknowledgement to Arthur Morris' book, The Art of Bird Photography),

I couldn't help but become conscious of others around me with comparable

equipment and wonder about their situations. Which ones were amateurs

like me and which ones were pros?

Then, one day as my wife and I were driving the loop

at our favorite refuge we spotted a very expensive SUV pulled off

on the shoulder ahead of us. I slowed down and took in the scene.

A rather distinguished and experienced looking gentleman was extracting a

big lens rig from the back of his SUV and setting up. I had already

looked over the marshy pool we were traversing and decided there wasn't

anything I wanted to spend time on, but this fellow looked the part so maybe

he knew something I didn't.

His gear was top of the line, compared to my photo vest his looked like a

dinner jacket, and his

SUV was, well, I wish I could have afforded it. In a sudden flash of

realization, it came to me. He was a pro! Then, one day as my wife and I were driving the loop

at our favorite refuge we spotted a very expensive SUV pulled off

on the shoulder ahead of us. I slowed down and took in the scene.

A rather distinguished and experienced looking gentleman was extracting a

big lens rig from the back of his SUV and setting up. I had already

looked over the marshy pool we were traversing and decided there wasn't

anything I wanted to spend time on, but this fellow looked the part so maybe

he knew something I didn't.

His gear was top of the line, compared to my photo vest his looked like a

dinner jacket, and his

SUV was, well, I wish I could have afforded it. In a sudden flash of

realization, it came to me. He was a pro!

In that moment, reason departed. Like groupies

everywhere, I just had to be a part of his world! As we came parallel,

I powered down the window on my wife's side, leaned across her and, as the

gentleman looked up from his big lens, I blurted out, "Have you seen

anything good to shoot?"

The look he have me in that moment can only be

described as one cold enough to turn every living creature in the refuge to

stone. In a flash of horrified realization, I saw my action for what

it was. I had unwittingly become what I decried in others!

I drove away as fast as circumstance permitted, face

burning with shame, and found a vantage at another pool as far as possible

within the confines of the refuge from the pro. Or, at least that's

what I took him for. Only an authentic pro could transfix you with that kind of

withering glare. Amateurs were peasants compared to such exalted

nobility. I drove away as fast as circumstance permitted, face

burning with shame, and found a vantage at another pool as far as possible

within the confines of the refuge from the pro. Or, at least that's

what I took him for. Only an authentic pro could transfix you with that kind of

withering glare. Amateurs were peasants compared to such exalted

nobility.

Eventually I found a cooperative great egret and set

up my own big lens rig. By now it was late afternoon and the light was

getting good. The only negative was that the sun was at an oblique

angle to the pool's bank so I had to set up a good distance from the egret

to get full frontal sun on the bird. This necessitated use of a teleconverter, but I was (and am) used to shooting with teleconverters when

needed so I settled in to take advantage of the situation.

Soon thereafter, to my dismay the very expensive SUV

pulled onto the shoulder in front of my location and directly across from the great egret.

At first I thought the pro had come for me, to tell me what a rank amateur I

was and how I should never speak to a real pro again, unless I had something

meaningful to say. Like name, rank and dog tag number or phone number

of next of kin. Then, I noticed that he was setting up his rig at

the location where he had parked. Hmm, I thought. That will

never do. From that location the egret is side-lit.

He's not going to get much there. Could it be that I've made a better

choice than a pro? Soon thereafter, to my dismay the very expensive SUV

pulled onto the shoulder in front of my location and directly across from the great egret.

At first I thought the pro had come for me, to tell me what a rank amateur I

was and how I should never speak to a real pro again, unless I had something

meaningful to say. Like name, rank and dog tag number or phone number

of next of kin. Then, I noticed that he was setting up his rig at

the location where he had parked. Hmm, I thought. That will

never do. From that location the egret is side-lit.

He's not going to get much there. Could it be that I've made a better

choice than a pro?

I soon dismissed the thought, put eye to

viewfinder again and clicked away busily. Some indefinite time

thereafter a voice caused me to look up. "It seems you've chosen the

best location to take advantage of the sun angle." It was the pro, and

he wasn't frowning! Amazingly, he chatted photography for a few minutes,

left me his business card (he really was a pro) and departed. The

final courtesy was that he did not intrude on my location, which I greatly

appreciated as good subjects weren't plentiful that afternoon.

As I reflected on the incident afterward I realized

that not everyone who behaves like a photo groupie is given an opportunity for

redemption. I was most appreciative of mine.

Learning to Live With Donkeys, Bless Their Pea-Pickin' Hearts!

Over the years I've had many people come up to me and

ask questions. From this, I've learned to accept -- grudgingly

-- and live with the fact that not everyone understands the intensity and

concentration with which I pursue bird photography in the field. When

people see a big lens they're just naturally drawn to it, and in most cases

it is an opportunity to educate and spread good will toward nature

photographers rather than to discourage them with a gruff dismissal.

The same thing is true with astronomical telescopes,

by the way. When I'm out with a scope I'm inevitably asked similar

questions. "How much did that cost?" "How far can you see with

it?" etc. Of course, in the case of the second question it's a little

trickier with a telescope. I'm tempted to reply, "Well, how far do you

want to see?" The question is so earthbound in its thought

process. If I'm feeling particularly curmudgeonly I'll reply

offhandedly, "Oh, millions and millions of light-years." The same thing is true with astronomical telescopes,

by the way. When I'm out with a scope I'm inevitably asked similar

questions. "How much did that cost?" "How far can you see with

it?" etc. Of course, in the case of the second question it's a little

trickier with a telescope. I'm tempted to reply, "Well, how far do you

want to see?" The question is so earthbound in its thought

process. If I'm feeling particularly curmudgeonly I'll reply

offhandedly, "Oh, millions and millions of light-years."

But a better answer would be to explain that in

astronomy "how far" isn't usually the important question. We're

limited by how much light our telescopes can gather and how bright, or

faint, if you prefer, our target object is. So a bright object a long

distance away can be just as visible as a dim object nearby. Of

course, this kind of generalization, while true, satisfies no one, and

pretty soon someone pipes up with, "What's the fartherest away thing you

can see?"

I

really should memorize a standard set of facts for such situations, but I'm

a first principles and big picture (pardon the obvious pun) kind of guy, so

the answer I've settled on is this. At an apparent magnitude of 12.9,

quasi-stellar radio source 3C 273 in the constellation Virgo is the

brightest quasar in our skies. Its red shift of 0.158 places it at

two billion light-years from us. At that magnitude 3C 273

should be

just within reach of a quality 4-inch refractor on a good night --

although one would struggle to find it against faint field stars, making it

a more suitable, albeit wholly uninteresting object ("quasi-stellar" means

it looks just like every star up there!) for larger scopes. I

really should memorize a standard set of facts for such situations, but I'm

a first principles and big picture (pardon the obvious pun) kind of guy, so

the answer I've settled on is this. At an apparent magnitude of 12.9,

quasi-stellar radio source 3C 273 in the constellation Virgo is the

brightest quasar in our skies. Its red shift of 0.158 places it at

two billion light-years from us. At that magnitude 3C 273

should be

just within reach of a quality 4-inch refractor on a good night --

although one would struggle to find it against faint field stars, making it

a more suitable, albeit wholly uninteresting object ("quasi-stellar" means

it looks just like every star up there!) for larger scopes.

However non-relevant it may be to enjoying an evening

of stargazing, two billion light-years seems to satisfy most questioners!

But, whether astronomy or photography the message is

this. Most individuals who approach someone with expensive gear does

so with a set of implicit expectations. They assume the person with the

gear a) knows what they are doing, and b) will be willing to share what they

know with some degree of polite tolerance. And rightly or wrongly,

they will form an opinion of all photographers based on how they are treated

during that interaction.

One could say that it doesn't matter what most people

think of us -- and one might even be right, most of the time. But,

inevitably there will be instances when someone is put off who could have

become a helpful friend to our community. Or someone is turned off to

nature who might have become an enthusiast. And, underneath it all,

for some of us there is a more personal question: What kind of person

do we want to be, one who shuts out others or one who welcomes the

opportunity to share with others a little of our knowledge about the

activity that brings us so much fulfillment. One could say that it doesn't matter what most people

think of us -- and one might even be right, most of the time. But,

inevitably there will be instances when someone is put off who could have

become a helpful friend to our community. Or someone is turned off to

nature who might have become an enthusiast. And, underneath it all,

for some of us there is a more personal question: What kind of person

do we want to be, one who shuts out others or one who welcomes the

opportunity to share with others a little of our knowledge about the

activity that brings us so much fulfillment.

So, the conclusion I have reached is this. If

birds can tolerate my presence in their world I can tolerate donkeys'

presence in mine!

© 2013 Michael W. Masters

Return to top

|